Overview Of Bacterial endocarditis

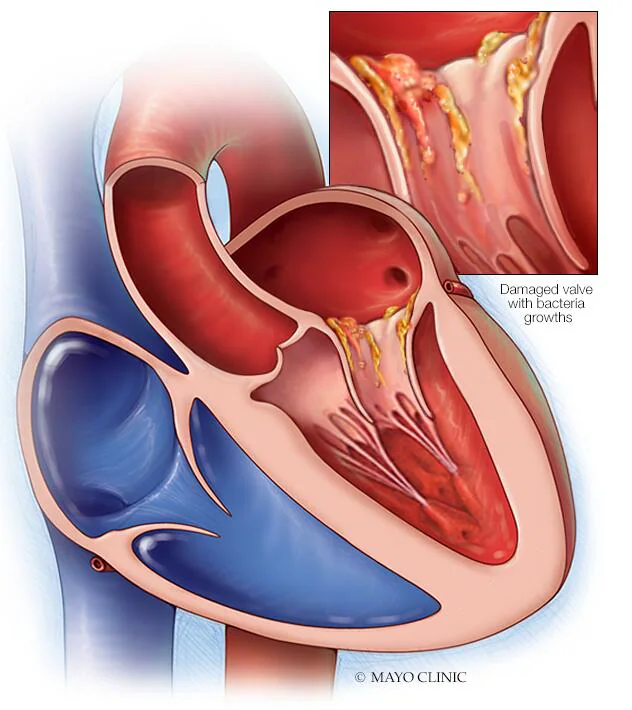

Bacterial endocarditis, also known as infective endocarditis (IE), is a serious infection of the endocardium, the inner lining of the heart chambers and valves. It occurs when bacteria enter the bloodstream and attach to damaged areas of the heart, forming vegetations (clumps of bacteria, fibrin, and blood cells). These vegetations can disrupt normal heart function and lead to life-threatening complications, such as heart failure, embolic events, or systemic infection. Bacterial endocarditis can affect individuals with pre-existing heart conditions, such as damaged heart valves or congenital heart defects, but it can also occur in those with no prior heart disease. The condition is classified as acute or subacute based on the severity and progression of symptoms. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to prevent severe outcomes.

Symptoms of Bacterial endocarditis

- The symptoms of bacterial endocarditis vary depending on whether the condition is acute or subacute. Acute endocarditis presents with rapid-onset symptoms, including high fever, chills, fatigue, and muscle aches. Patients may also experience shortness of breath, chest pain, or a new heart murmur due to valve damage. Subacute endocarditis develops more gradually and may cause nonspecific symptoms such as low-grade fever, night sweats, weight loss, and generalized weakness. Other clinical features include petechiae (small red or purple spots on the skin), Osler’s nodes (painful nodules on the fingers or toes), Janeway lesions (non-tender macules on the palms or soles), and splinter hemorrhages under the nails. Embolic events, such as stroke or pulmonary embolism, can occur if vegetations break off and travel through the bloodstream.

Causes of Bacterial endocarditis

- Bacterial endocarditis is primarily caused by bacteria entering the bloodstream and colonizing the endocardium. The most common causative organisms include *Streptococcus viridans*, *Staphylococcus aureus*, and *Enterococcus* species. *Staphylococcus aureus* is particularly associated with acute endocarditis, often affecting individuals with no prior heart disease, while *Streptococcus viridans* is more common in subacute cases, typically involving pre-existing valvular abnormalities. Bacteria can enter the bloodstream through various routes, such as dental procedures, invasive medical interventions, intravenous drug use, or infections in other parts of the body (e.g., skin, urinary tract). Individuals with prosthetic heart valves, pacemakers, or congenital heart defects are at higher risk due to the increased likelihood of endothelial damage and bacterial adherence.

Risk Factors of Bacterial endocarditis

- Several factors increase the risk of developing bacterial endocarditis. Pre-existing heart conditions, such as damaged or prosthetic heart valves, congenital heart defects, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, are significant risk factors. Invasive medical procedures, including dental work, surgery, or the use of intravascular catheters, can introduce bacteria into the bloodstream. Intravenous drug use is a major risk factor, particularly for right-sided endocarditis involving the tricuspid valve. Poor dental hygiene and chronic skin infections can also increase the likelihood of bacteremia. Other risk factors include advanced age, diabetes, and a history of previous endocarditis. Immunocompromised individuals, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or with HIV, are at higher risk due to reduced immune defenses.

Prevention of Bacterial endocarditis

- Preventing bacterial endocarditis involves reducing the risk of bacteremia and managing underlying risk factors. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for high-risk individuals undergoing dental or invasive procedures that may cause bacteremia. High-risk groups include those with prosthetic heart valves, previous endocarditis, certain congenital heart defects, or cardiac transplants with valvulopathy. Maintaining good oral hygiene and promptly treating infections, such as skin or urinary tract infections, can reduce the risk of bacteremia. Intravenous drug users should be educated about the risks of endocarditis and encouraged to seek treatment for substance use disorders. Regular follow-up with a healthcare provider is essential for individuals with pre-existing heart conditions to monitor for early signs of infection.

Prognosis of Bacterial endocarditis

- The prognosis for bacterial endocarditis depends on several factors, including the causative organism, the extent of heart damage, and the timeliness of treatment. With early diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic therapy, the mortality rate for native valve endocarditis is approximately 10–20%, but it increases to 20–40% for prosthetic valve endocarditis. Complications such as heart failure, embolic events, or abscess formation significantly worsen the prognosis. Delayed treatment or antibiotic resistance can lead to persistent infection or relapse. Long-term outcomes are improved with adherence to treatment, surgical intervention when necessary, and management of underlying risk factors. Survivors may require lifelong monitoring for recurrent infection or valve dysfunction.

Complications of Bacterial endocarditis

- Bacterial endocarditis can lead to severe and potentially life-threatening complications. Heart failure is a common complication due to valve damage or destruction, leading to impaired cardiac function. Embolic events, such as stroke, pulmonary embolism, or splenic infarction, can occur if vegetations break off and travel through the bloodstream. Abscess formation in the heart or surrounding tissues may require surgical drainage. Other complications include septic shock, acute kidney injury due to immune complex deposition, and mycotic aneurysms caused by infected emboli. Prosthetic valve endocarditis is particularly challenging, as it often involves more virulent organisms and a higher risk of complications. Chronic complications may include recurrent infections, valve dysfunction, or the need for lifelong anticoagulation therapy.

Related Diseases of Bacterial endocarditis

- Bacterial endocarditis is closely associated with several other conditions and complications. It shares risk factors with other cardiovascular diseases, such as valvular heart disease, congenital heart defects, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The condition is also linked to systemic infections, including sepsis and abscesses in other organs. Non-infective endocarditis, such as Libman-Sacks endocarditis associated with lupus, can mimic bacterial endocarditis but requires different management. Rheumatic fever, a complication of untreated streptococcal infections, can lead to valvular damage and increase the risk of bacterial endocarditis. Additionally, conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as HIV or chemotherapy, can predispose individuals to infections, including endocarditis. Understanding these related diseases is essential for comprehensive prevention and treatment strategies.

Treatment of Bacterial endocarditis

The treatment of bacterial endocarditis involves prolonged antibiotic therapy tailored to the causative organism. Intravenous antibiotics are typically administered for 4–6 weeks to ensure complete eradication of the infection. Empirical therapy often includes a combination of antibiotics, such as vancomycin and ceftriaxone, until blood culture results are available. For methicillin-resistant *Staphylococcus aureus* (MRSA), vancomycin or daptomycin is used. Surgical intervention may be necessary in cases of severe valve damage, heart failure, persistent infection, or large vegetations at risk of embolization. Surgery may involve valve repair or replacement, drainage of abscesses, or removal of infected prosthetic material. Supportive care, including management of heart failure or embolic complications, is also critical. Close monitoring and follow-up are essential to prevent relapse or complications.

Generics For Bacterial endocarditis

Our administration and support staff all have exceptional people skills and trained to assist you with all medical enquiries.

Amoxicillin

Amoxicillin

Amphotericin B

Amphotericin B

Ampicillin

Ampicillin

Azithromycin

Azithromycin

Benzyl Penicillin

Benzyl Penicillin

Ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone

Cephalexin

Cephalexin

Gentamicin

Gentamicin

Streptomycin

Streptomycin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin

Amoxicillin

Amoxicillin

Amphotericin B

Amphotericin B

Ampicillin

Ampicillin

Azithromycin

Azithromycin

Benzyl Penicillin

Benzyl Penicillin

Ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone

Cephalexin

Cephalexin

Gentamicin

Gentamicin

Streptomycin

Streptomycin

Vancomycin

Vancomycin